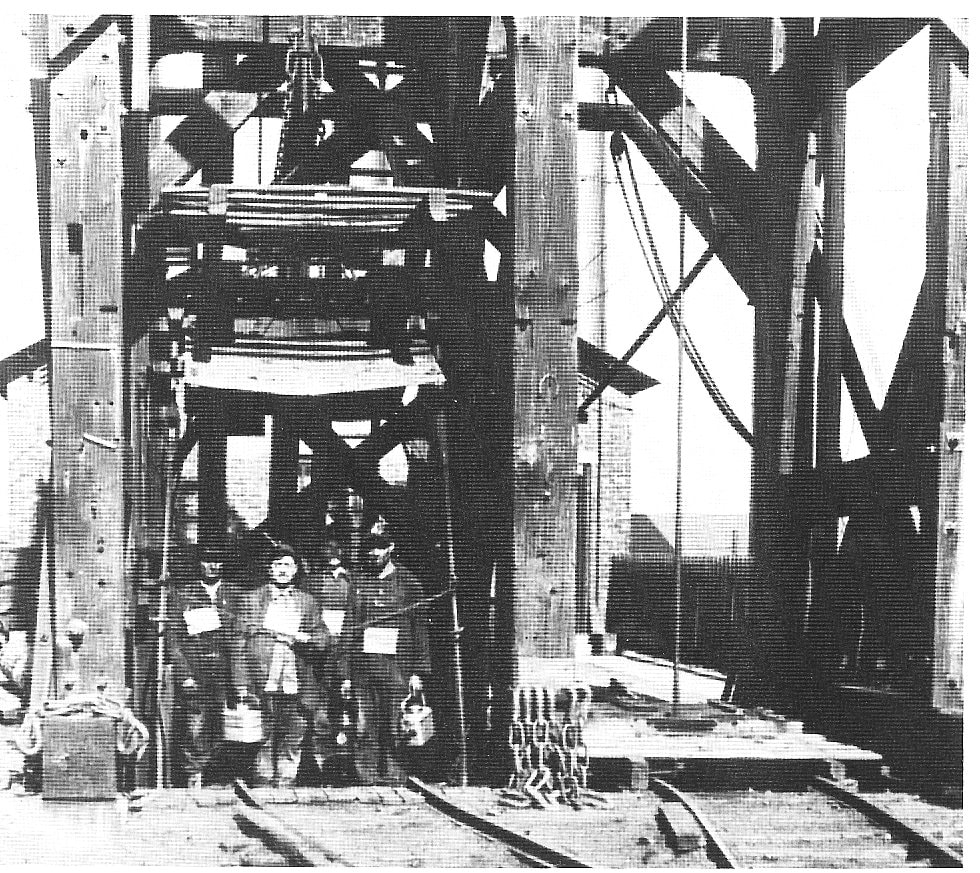

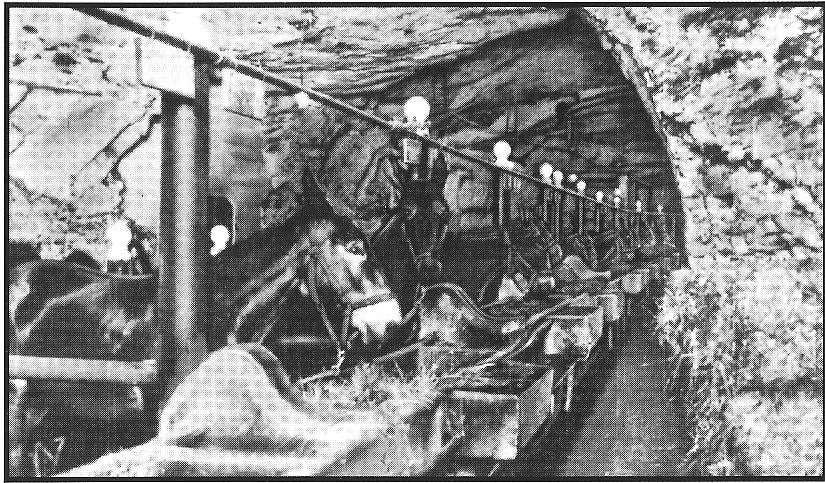

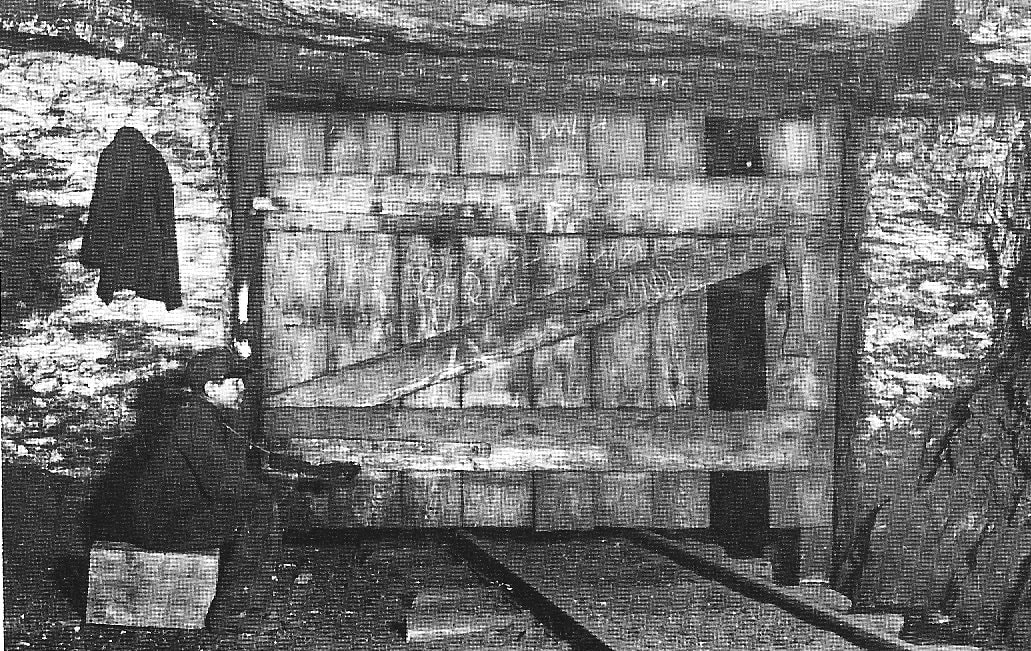

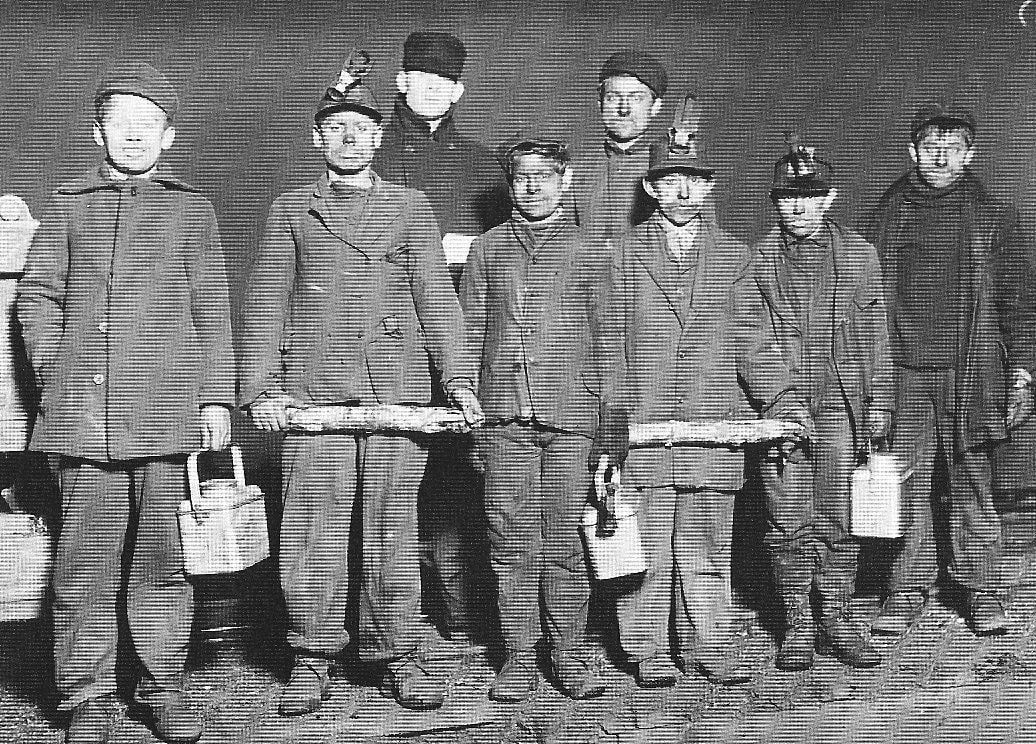

Black Hell Drowning, "Miner's Lament," and A Writing GiftAs I posted in my last newsletter, I am sending these announcements when there is some significant development, or I have something to share that I think you will find interesting and/or useful. In this one, I want to give you a writing gift. My father was a coal miner and Black Hell Drowning is a story about life and death in the anthracite coal mines of Pennsylvania. I have been doing some rewriting of that manuscript and, as I continue, my intention is to share it directly with you. For this one, I wanted to share something I did finish regarding coal mining. A Writing Gift for You; "Miner's Lament"In addition to writing long-form novels, I less-often try my hand at writing poetry and short stories. Once in a great while, I submit my writing to contests. My poem, "Miner's Lament," won third place in the world-wide Writer's Digest competition in 2015. Now I am including it here followed by an explanation of the terms and illusions in the poem. I trust my comments will greatly enhance your understanding and pleasure in reading it. I recommend that you read the poem first, then read the explanations, then re-read the poem again. Once you have read the explanations, I think you will have a completely different and much more satisfying experience reading the poem the second time around. I would also welcome and appreciate your questions and comments. Now here is "Miner's Lament." Miner's LamentPink: the color of sky, blossom, organ. Pink, the day education ended and heaven faded to black in a cage dropping six hundred feet. Pink, invisible in the darkness save the lamps lighting the way of blind mules, fat rats and sacrificial birds. Dark pink after a year, waiting in the blackness for each mule, opening , closing, salvaging precious air. Light grey after three years, straddling chutes in the breaker’s deafening roar, sifting stones in the black clouds. Grey after seven years, racing alongside two-tons of runaway coal car with only sprags to stop them. Dark gray after twenty years, surviving black damp, white damp, falling bells and singing timbers. Black after thirty years, wheezing up blood and never smoked a damn day in my life. The Meaning Behind "Miner's Lament"My father was an anthracite coal miner in Pittston Pennsylvania, as was my older brother Nick and many other uncles, cousins and friends. This poem was inspired by and dedicated to them and their spouses (like mom, pictured above with dad) and their families. Now here is the meaning behind "Miner's Lament." Miner's Lament: What's in the Title? The title of this poem serves an important function. It tells us that everything in the poem itself relates directly to a miner. In addition, the word lament tells us that this poem focuses on something for which the miner is expressing regret. Keep this in mind as you read it. Pink: the color of sky, blossom, organ. Pink, the day education ended and heaven faded to black in a cage dropping six hundred feet. I'll expand on the color references toward the end. I expect you might have figured them out for yourself by then. I'll start here with the second stanza, My father was eleven years old "the day education ended." He was pulled out of school in the fourth grade to work in the mines. Like many boys in mine-country, his income was needed to support the family. The elevators that were used to take miners down to the mine and carry the coal cars back up were called cages. In Pittston, many of the anthracite coal veins were six hundred or more feet underground. If you looked out the top of the cage as you descended, the early-morning pink sky above would darken and eventually disappear completely as "heaven faded to black." Pink, invisible in the darkness save the lamps lighting the way of blind mules, fat rats and sacrificial birds. Without light, the darkness in the mines is absolute. You literally cannot see your hand in front of your face. Before the introduction of "electric motors" to pull the coal cars from the working face to the cages, mules were used. Stables were hune out of the rock in the mine, and many mules spent their entire lives underground. Eventually, the mules went blind because of the dim surroundings. If you asked a miner what he would do if he saw a rat, his answer would be to "feed it." Many miners believed that in the event of a cave-in or flood, the rats would sense the danger, so if the miners saw the rats running, they would start running too. There were many forms of poisonous gases in the mines. Many of us have heard the expression "the canary in the coal mine." Before the advent of gas detectors, miners often brought canaries with them to work. Since the bird's lungs would succumb to the gas sooner then the miner, if his "sacrificial bird" collapsed, the miner would immediately leave the area. Dark pink after a year, waiting in the blackness for each mule, opening , closing, salvaging precious air. Young boys working in a mine complex or "colliery" usually started out above ground working as "breaker boys." One of the first jobs a boy was given within the mine itself was that of a door-boy or "nipper." Mines could stretch out for miles underground in a maze of shafts and tunnels. Huge exhaust fans forced fresh air from the surface through the mine. It was crucial that the air be channeled to those areas where the miners were working, otherwise they could suffocate to death. To accomplish this, heavy doors were installed to cut off the sections of the mine that were already "worked out." It was the nipper's job to open the door only when a coal car was coming through and close it immediately afterwards, thus "salvaging precious air." Before electric lights were installed, the only light the nipper had came from the head-lamp on his helmet. In order to save the light for when it was most needed, the nipper would "wait in the blackness" with only the rats to keep him company. If he fell asleep and didn't open the door in time, a mule might crash through, slamming the heavy door against the sleeping boy. Light grey after three years, straddling chutes in the breaker’s deafening roar, sifting stones in the black clouds. The first job many young boys had in a colliery was that of a "breaker boy." The breaker was a huge, tall building that served as the heart of the mine complex. Coal cars were transported to the top of the breaker where they dumped their load of coal and stone. The load worked its way down via chutes. Breaker boys sat "straddling chutes in the breaker's deafening roar" and separated the stones from the coal. The stones were dumped into huge mounds called culm piles. The chunks of coal continued downward into the metal grinding wheels that broke the chunks into various sizes for different commercial and residential applications. The coal exited the bottom of the breaker into gondola train cars for transportation throughout the country. The fingers of newer breaker boys would bleed until they became calloused and the coal dust from the constantly churning grinders submerged the boys in "black clouds." Workers with sticks supervised the breaker boys and hit any who appeared to be falling asleep. If a boy nodded off and fell into a chute, he could be drawn into the breaker and crushed to death. Grey after seven years, racing alongside two-tons of runaway coal car with only sprags to stop them. A loaded coal car weighed several tons. Before the cars were equipped with breaks, a worker, usually an older boy, was assigned to slow or stop the car manually using a wooden wedge called a sprag. The worker would run alongside the car and insert the sprag between the wheels and the body of the coal car. If they missed their mark, they risked losing an arm or leg. My uncle Sam recounted a time when he rode atop a car and his sprag didn't hold. He rode the runaway car to the breaker and jumped up to catch the door railing just as the car crashed into the breaker. He lost his job but not his life. Dark gray after twenty years, surviving black damp, white damp, falling bells and singing timbers. There are multiple ways to die in a mine. As I mentioned earlier, there are many forms of poisonous gases. Carbonic acid, or "black damp," is fatal in large doses. When exposed to fire, it becomes carbonic oxide, or "white damp," and is fatal in even small concentrations. Often in mines, a chunk of rock will loosen and fall from the ceiling. The rock often took the shape of a bell and could be smaller than a breadbox or larger than a chair. Landing on a man, a "falling bell" could cripple or kill him instantly. My brother Nick narrowly missed having one fall on him when he heard something odd and quickly stepped out of the way. Seeing pictures of timbers in mines can mistakenly lead us to believe that they are preventing the mine from caving in. Apart from holding loose rock from falling, the weight above a mine several hundred feet below the surface would quickly destroy even the strongest timbers. Prior to a cave-in however, the ceiling can shift, exerting its weight on the timbers. When that happens, the "singing timbers" will emit a loud cracking sound which can give the miners time to evacuate before the ceiling comes crashing in. Black after thirty years, wheezing up blood and never smoked a damn day in my life. My father worked in the mines for many years, ending up as an electrician and working on the motors that replaced the mules for pulling the coal cars out of the mines. He left the mines and tried to start his own business, working for a time as an independent appliance repairman in Pittston. When I was six, he moved our family to Brooklyn, New York and took a job as a factory worker, so his children would have the opportunity to earn a living without having to work in the mines or dress shops. That however, did not save him from his years in the coal dust. For years, he struggled with his breathing and shortly after retiring died of the "black lung" disease. By now, I expect that many of you have figured out that the colors referred to in the poem relate to the lungs of those who worked in the mines. I often wonder how many other writers, poets, artists, and others were never able to express their creativity because they never got the opportunities my father gave us. For that, I will be forever grateful. Now that you know the meaning behind the poem, I invite you to read it again and visualize the meaning of each sentence. I trust it will be a completely different experience. Now, here again, is Miner's Lament. Pink: the color of sky, blossom, organ. Pink, the day education ended and heaven faded to black in a cage dropping six hundred feet. Pink, invisible in the darkness save the lamps lighting the way of blind mules, fat rats and sacrificial birds. Dark pink after a year, waiting in the blackness for each mule, opening , closing, salvaging precious air. Light grey after three years, straddling chutes in the breaker’s deafening roar, sifting stones in the black clouds. Grey after seven years, racing alongside two-tons of runaway coal car with only sprags to stop them. Dark gray after twenty years, surviving black damp, white damp, falling bells and singing timbers. Black after thirty years, wheezing up blood and never smoked a damn day in my life. Thank you for spending this time with me. I hope that you found this to be of interest and hopefully, value. I would love to hear your reaction and I welcome you comments, questions and suggestions. You can write to me via the "contact" page of my website, AuthorChuckMiceli.com. On that same site you will find information about my other writings and you can learn much more about my most recent book, Wounded Angels at my book website, WoundedAngelsBook.com. Until the next time, I hope this finds you and yours happy and healthy.

Warmest Regards, Chuck

0 Comments

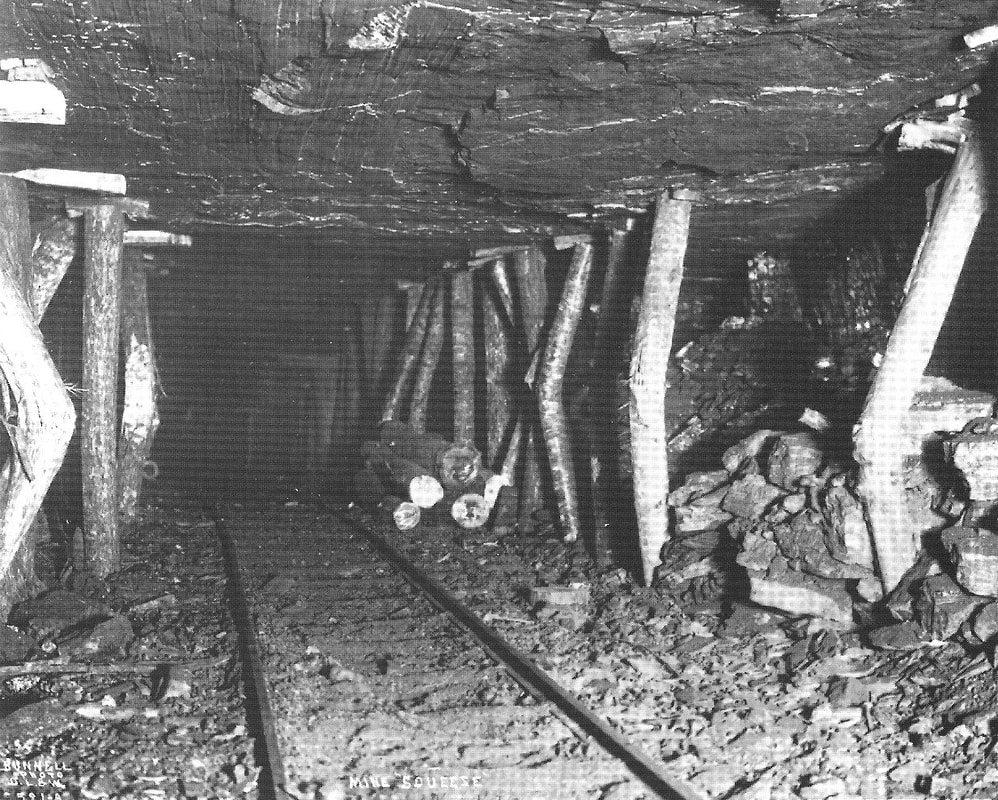

|

AuthorChuck Miceli works like hell to write heavenly novels Archives

January 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed